- La Garde Ecossaise Historical Fiction and Early Modern Studies

- Posts

- La Garde Ecossaise Historical Fiction and Early Modern Studies Newsletter

La Garde Ecossaise Historical Fiction and Early Modern Studies Newsletter

No. 11 Life in an Early Modern French Village

Welcome

A warm welcome to the La Garde Ecossaise Historical Fiction newsletter – this is your fortnightly update on the novel series and early modern studies.

New Releases from La Garde Ecossaise

Audio Guide Chapter 15 [6] The Meeting

Audio Guide Chapter 16 [7] Elouise

Audio Guides can be found on Spotify, Apple Podcasts and YouTube.

Quote

‘Le Pecq is a small village on the edge of the river directly across from the chateau. My first impression of Le Pecq that there was nothing spectacular about it. It was just a series of winding streets with close knit houses all huddled together. As I have already described, we lived in a row of houses along one street where they had been carefully positioned. We could see into each other’s houses and apart from it being a place where staff from the Chateau lived, it also had a spring which provided clean water. It was a small tight knit community living in the shadow of the Chateau of St Germain’. La Garde Ecossaise Book 1 p.63.

David Teniers, Village Revel with Aristocratic Couple 1652, Louvre Museum, Paris, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Early Modern Digest

England’s ‘first refugee policy’ in the sixteenth century https://eastangliabylines.co.uk/lifestyle/history/this-16th-century-law-was-englands-first-refugee-policy/

Decoding Diego’s Velazquez’s Les Meninas https://mymodernmet.com/diego-velazquez-las-meninas/

Painting of Louis XIV’s coronation found in English stables https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-tees-37660296

What 17th century nuns can teach us about loneliness https://theconversation.com/a-not-so-modern-epidemic-what-17th-century-nuns-can-teach-us-about-coping-with-loneliness-249487

The experience of English immigrants in the Virginias and Carolinas in the 17th century. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/17th-century-english-who-settled-southern-us-had-very-little-be-thankful-180953466/

Did You Know?

Jerusalem was an administrative centre in the Ottoman Empire during the early modern period in which lived Jews, Christians and Muslims. The Christians being infidels had to pay a special poll tax. A surviving poll tax roll from 1691 offers a valuable insight into the lives of Christians in Ottoman Palestine. Palestine is the Islamic name for Palestina Prima, which derives from the Roman name for the Jewish land of Israel. See more about the poll tax from 1691 here: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3632370

Map of Jerusalem c.1658 National Library of Israel via Wikimedia Commons.

Feature Article: Life in an Early Modern French Village

In La Garde Ecossaise we are introduced to the village of Le Pecq which was a village located on the opposite side of the river to the Palace of St Germain en Laye. Today, it is a bustling and vibrant town but back in the early modern period it was a small village that lived in the shadow of the royal palace. Meldrum paints a vivid description of the village, its key buildings and some of its inhabitants. (See quote above). It is clear from this description that the village was its own community with key features that would have been common in many villages throughout France, a church, an inn and a landed estate or landowner who set the tone for life in the village for its inhabitants.[1]

This feature article will attempt to convey the importance, structure and dynamics of French village life in the early modern period. The last section of the article will reflect on Marly-le-Roi and Le Pecq and their relationship with the ‘royal domaine’ , reflecting upon how this differentiated them from non-royal domaine villages in ancien regime France.

The Importance of Rural Communities in Early Modern France

Early modern France was an overwhelmingly agricultural economy with an estimated 9 out of 10 French subjects living in the countryside. Although, there were urban centres and industry in early modern France, cities and towns were focused on specific activities, trade or administrative functions. Early modern France was dominated by swathes of farmland and village communities. As farming was the bedrock of these communities, they were often at the mercy of crop failures and bad weather which, in turn, would cause a rise in prices. Many peasants in rural areas often faced with these challenges would become malnourished or in the most extreme cases starve to death. Disease, hard labour and undernourishment were commonplace amongst rural communities in France. Yet, the agricultural and food economies were the backbone of French society with peasants being the largest consumers of French produce.[2]

Le Nain Brothers, Peasants at their Cottage Door, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco via Wikimedia Commons.

The reality of life in France for the majority of the population was detailed in a report from the Estates of Normandy in 1651:

‘Of the 450 sick persons whom the inhabitants were unable to relieve, 200 were turned out, and these we saw die one by one as they lay on the roadside. A large number still remain, and to each of them it is only possible to dole out the least scrap of bread. We only give bread to those who would otherwise die. The staple dish here consists of mice, which the inhabitants hunt, so desperate are they from hunger. They devour roots which the animals cannot eat; one can, in fact, not put into words the things one sees.... This narrative, far from exaggerating, rather understates the horror of the case, for it does not record the hundredth part of the misery in this district. Those who have not witnessed it with their own eyes cannot imagine how great it is. Not a day passes but at least 200 people die of famine in the two provinces’.[3]

The Feudal Structure of the French Village

The foundational structure of the French village, as it was throughout the majority of western Europe, was based on feudalism. In a medieval context, and in its most basic form feudalism was a defined structure with the King at the top of the societal pyramid, who gave lands to nobles, who in turn, employed peasants to work on the land. Thus, the feudal pyramid would look like this:

Javelot1, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

French villages were divided between the landed elite, the nobles or landlords and the peasants. The nobles would preside over local village courts known as seigneurial courts and intervene in the village’s disputes. The nobles and the landlords had the power to collect revenues from peasants.[4]

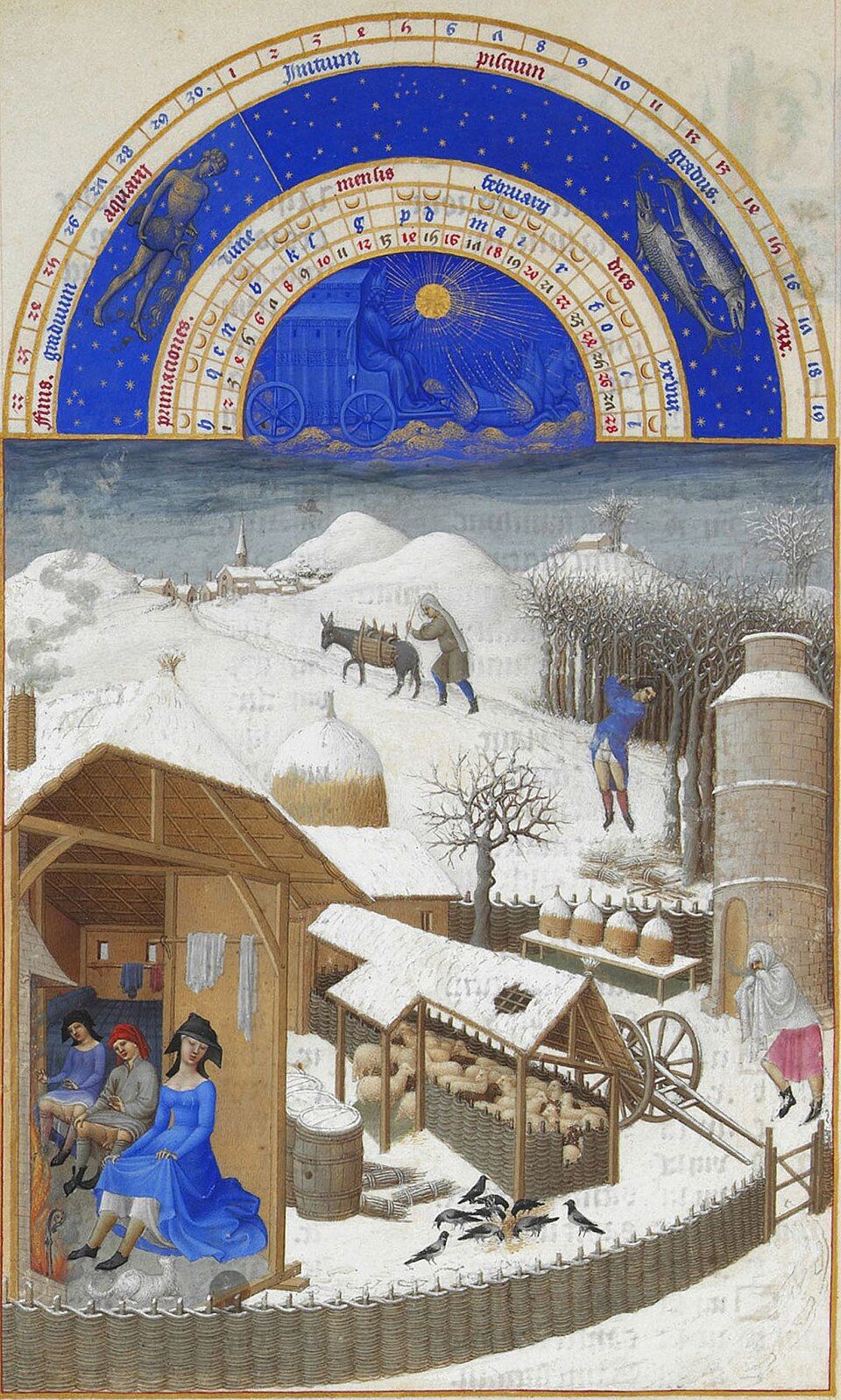

Très Riches Heures de Duc de Berry

A beautiful and detailed book from the fifteenth century illustrates the difference between the rich and playful lifestyle of French nobles and the harsh life experienced by French peasants. At the top of the page are the constellations which refer to the ‘great chain of being’, the social order and the seasons of the year. Each picture illustrates in detail a month in the life of nobles and peasants. In particular, the peasant image at winter, illustrates just how harsh and cruel life could be in the French countryside.

Take the time to examine the two contrasting images here:

Nobles - January

Limbourg Brothers via Wikimedia Commons

Peasants - February

Limbourg brothers, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

This structure continued from the medieval to the early modern periods but by the early modern period, village society had become far more mobile and diverse. Early modern villages also contained artisan industries such as ‘cobblers, tailors, barrelmakers, ropemakers and carpenters’.[5] Early modern villages were not self-contained communities but would be influenced by and would influence surrounding and connected communities. Mobile populations would include clergymen transferred or planted from other parishes, travellers passing through the village, landed gentry outside the local area who would purchase land, landless poor and vagrants who would travel from parish to parish in search of work and sustenance.[6]

The Dynamic Layers of French Village Life

French villages were not sleepy backwater communities but constantly evolving organic communities that were made up of several interconnected and overlapping communities and obligations which played a pivotal role in shaping French village life.

Church, Parish Life and Clergy

The parish church was the one institution that parishioners within the village would be familiar with throughout their life. The local priest would administer the sacraments that would mark the various stages between birth and death, baptism, first communion, marriage and funeral rites. It was commonplace to live in the same village as your forebears (although not always the case) and be buried with other family members. Religion in French villages, despite a drive from the clergy for a godly society was a curious mix of Christian religion belief, pagan tradition and local folklore. The religious calendar also dominated the life of French villagers as it was marked by the weekly divine service, confessionals and saints’ days. The church was seen as a place of refuge and advice should the parishioner run into spiritual or financial difficulty which could exonerate sins as well as provide money to parish members or the poor. As Gail Bossenga states the French parish church could be used to organise protests and demonstrations, ‘A majority of protests in the old regime began on Sunday after Mass when peasants had an opportunity to discuss their grievances’. [7]

Le Nain Brothers, A Landscape with Peasants and a Chapel, Wadsworth Museum of Art via Wikimedia Commons.

Agricultural

The agricultural communities did not just consist of those who farmed the land but also of labourers who were brought in on a temporary or short-term basis to work the land when required and at the other end, managers who were the contact between the farmer and the landlord. If the labourer got into financial difficulty, he would often borrow money from money lenders who would benefit from the ups and downs of the labourer’s life.[8] In addition the agricultural community was also part of a wider economic market in foodstuffs, not just amongst the villagers themselves as consumers, but also the wider surrounding areas including those who bought and sold animals and equipment in the local area. If your village or farm was located near an urban centre, it would have access to weekly markets and an opportunity to sell goods to a population largely dependent upon the importation of foodstuffs from the surrounding countryside.[9]

Trades and Artisans

Spinning wool and weaving were common small industries to be found in villages throughout France. There were also those who would act as salesmen for raw goods such as grain or finished goods such as wine.[10] As already discussed, it is likely that there were also ‘cobblers, tailors, barrelmakers, ropemakers and carpenters’.[11] In addition, it is likely that a village had its own farrier to ensure horses had the appropriate horseshoes for working and transportation.[12]

The Masterless Poor

The masterless poor were those who could not work hard and earn enough to survive and were often destitute. These were people who often did not have certain skills or were able to work long enough to gain those skills. They went from job to job turning their hand to anything. They were known by various names including gagne-deniers (penny earners) or gens de bras, hommes de peine. Every French village had these struggling and temporary workers, but they often did the hard labour for little pay.[13]

Travellers

Travellers passed through villages on their way to other places. The village would often have an inn or if part of the nobility, an apartment belonging to the lord or lady of the village where travellers could stay overnight and/or have a meal and refreshments. However, this was not necessarily a pleasant experience as this account from Bussy-Rabutin, testifies:

“We were received in a room on a lower level than the yard, and I am fully assured that the walls of the apartment are damp in the dog-days. Most of the tiles which had once paved it were lacking, so that one was compelled to steer a devious course across the floor. While the trees which were to serve us as fuel were being cut down, we were invited to sit down in enormous chairs, quite innocent of upholstery in front of a fireplace in which there was no fire. We languished in cold and dreary silence.’ [14]

Clearly those at the top of the social structure could be impoverished too.

Families and Households

This was the bedrock of the village community and the family unit was central to village life in early modern France. However, as historian William Beik states, often households were more than just parents and children:

‘Often there were other persons living under the same roof, who might be servants, farmhands, grandparents or a variety of cousins and other persons related by blood. There might also be several families living together, headed by two brothers, especially on remote farms needing more hands to maintain’.[15]

Antoine Le Nain, A Peasant Family, MET MUSEUM via Wikimedia Commons

Schoolmasters

These were appointed by the church and overseen by the parish clergy. The schoolmaster in the village would be responsible for a small number of children, at various stages of their education at any given time. The school itself would consist of a room in the building where the schoolmaster lived, rather than a dedicated schoolhouse. Formal education in French villages was for male children, with little, if any formal education for girls.[16]

Lords and Intendants

At the top of the village social structure was the lord or noble who owned the large estate or manor house in the local area. Furthermore, the lord could indirectly own land through leasing it to the gentry and other interested parties. The lord or noble’s outlook, priorities and ambitions had a bearing on the life of people living the villages under his authority. He could take a direct or active interest in the affairs of the village but in the early modern period many landed nobles began pursuing interests elsewhere and increasingly saw the village solely as a source of income. Often the landed nobility had intendants who would act as managers of their behalf allowing them to pursue interests elsewhere.[17]

This is a brief overview and future newsletters will be explore these groups in greater detail.

The Royal Domaine: the examples of Marly le Roi and Le Pecq

However, the two main French villages we encounter in La Garde Ecossaise are located in what was known as the ‘Royal Domaine’ and therefore functioned slightly differently to the majority of French villages.

The term ‘royal domaine’ does not just refer to the lands and property which the French kings owned for their own use, but lands which French kings used for state or public uses. The seventeenth-century definition of ‘domain’ is built around the feudal structure of lords and vassals, and this would still apply in a royal context, but also describes inherited property imbued with history and heritage. Again, given that royal property was inherited and were often buildings and lands of historical significance this definition of ‘domaine’ also applies when examining royal lands and estates.[18]

In the case of Marly-le-Roi, the village only existed to service the needs of chateau of the same name. That was the village’s sole purpose. Maps and images from Marly-le-Roi in the seventeenth century are dominated by maps of the royal estate and images of the chateau. Any architectural plans were drawn to enhance the chateau or provide accommodation for staff, including the Garde du Corps. It is also clear that Marly-le-Roi was a place from which the monarch issued Royal decrees to the rest of France. When the king was in residence Marly-le-Roi became a centre of royal power and administration. This marked it out from most French villages in France. Indeed, many travellers would have passed through the village of Marly-le-Roi without second thought on their way to the palace. The chateau and the King himself, when he was in residence, was the ultimate attraction. In contrast, to other villages, the population would have increased substantially when the King was in residence as courtiers, staff and the military all had to attend the King. In this regard, Marly-le-Roi was not unique, as St Germain en Laye and Versailles experienced similar fluctuations before 1682, before the court was permanently located in Versailles. During this time, the skills amongst the residents of the village, were different from most French villages as royal groomsmen, barbers and guardsmen would have walked the village streets.[19]

By Clicsouris - Own work, CC BY-SA 2.5, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=2181127

Marly-le-Roi should be contrasted with the fortunes of Le Pecq which although adjacent to the royal chateau and town of St Germain en Laye was not seen as a royal residence. Le Pecq in many ways resembled a normal French village with its church, housing and farming communities. However, given its position between the Royal Domaine and the city of Paris it was connected to both as an extension of the Royal Domaine and as a key resource that could benefit both the Royal Domaine and the City of Paris. For example, Henri IV wished to extend the gardens of the new chateau at St Germain en Laye and in doing so he expanded the gardens and annexed land that was originally part of Le Pecq. We also know that Le Pecq was used as an ‘overspill’ hosting aristocrats and bishops hoping to meet the king without a formal appointment or who were not part of the formal court structure. Paris acquired wood around the village for building projects within the city.[20]

I hope you have enjoyed the latest edition of the newsletter. If you are reading this newsletter on the web and have any questions please leave a comment below or you can email me at [email protected]

A Journey through Early Modern History. The La Garde Ecossaise Historical Fiction Novels. An introduction to early modern history as told through the power of historical fiction.

BUY from Amazon, Barnes and Noble and other retailers. Visit the official website for further details.

SUBSCRIBE to the official newsletter here to receive free short original articles and news on early modern history.

[1] Kirsteen M MacKenzie, La Garde Ecossaise (Aberdeen, 2022) 63-68.

[2] William Beik, A Social and Cultural History of Early Modern France (Cambridge, 2009) 15; Robin Briggs, Early Modern France 1560-1715 (Oxford, 1977) 33-37; Sharon Kettering, French Society 1589-1715 (Abingdon, 2014 ) 36.

[3] Internet History Sourcebook , ‘From the Report from the Estates of Normandy 1651’ https://sourcebooks.fordham.edu/mod/17france-soc.asp accessed 15 June 2025.

[4] Beik, A Social and Cultural History of Early Modern France 25-40.

[5] Thomas W. Robisheaux, ‘The World of the Village’ in Thomas A. Brady Jr, Heiko A. Oberman and James D. Tracey eds., Handbook of European History 1400-1600: Late Middle Ages, Renaissance and Reformation Volume I : Structures and Assertions (Leiden, 1994) 79.

[6] Robisheaux ‘The World of the Village’ 95-96.

[7] Briggs, Early Modern France 170-176: Gail Bossenga ‘Society’ in William Doyle ed., Old Regime France (Oxford, 2001) 55, 68.

[8] Briggs, Early Modern France 37-39.

[9] Robisheaux ‘The World of the Village’ 92.

[10] Kettering, French Society 42,

[11] Thomas W. Robisheaux, ‘The World of the Village’ in Thomas A. Brady Jr, Heiko A. Oberman and James D. Tracey eds., Handbook of European History 1400-1600: Late Middle Ages, Renaissance and Reformation Volume I : Structures and Assertions (Leiden, 1994) 79.

[12] Jacques de Solleysel, The parfait mareschal, or Compleat farrier. Which teacheth, I. To know the shapes and goodness, as well as faults and imperfections of horses (Edinburgh, 1696).

[13] James R. Farr, The Work of France: Labor and Culture in Early Modern Times (New York, 2008) Loc 758. [Kindle].

[14] Cecile Hugon, Social France in the XVII Century (London, 1911) 218-219.

[15] Beik, A Social and Cultural History of Early Modern France 58.

[16] Hugon, Social France in the XVII Century 229-230.

[17] Beik, A Social and Cultural History of Early Modern France 25-41; Bossenga ‘Society’ 68.

[18] Le Robert Dictionaire, ‘Domaine’ https://dictionnaire.lerobert.com/en/definition/domaine Accessed 16/06/2025.

[19]BnF Gallica, Drawing of King’s Bedchamber at the Chateau de Marly https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b55000877r.r=Marly%20le%20Roi?rk=21459;2; BnF Gallica, Declaration du Roy from Marly https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b8605972p.r=Marly%20le%20Roi?rk=171674;4; BnF Gallica, Stable Yard of the Garde de Corps at Marly https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b525227562/f1.item.r=Marly%20le%20Roi

[20] Le Pecq [Official Website] https://www.ville-lepecq.fr/decouvrir-le-pecq/lhistoire-du-pecq-2/ accessed 17 June 2025 ; Louis XIV, Edict du Roy, Portant création de cent Commissionnaires, Inspecteurs, Contrôlleurs, aux Empillements des Bois dans la ville, Faubourgs, & Banlieue de Paris (Versailles, 1706) 1 ; Reponse de M. l'archevesque de Rouen, à un factum diffamatoire composé par le feu sieur Corné, sur les faussetés contenuës audit factum. ( Paris, 1677-1690) 9.

Reply