- La Garde Ecossaise Historical Fiction and Early Modern Studies

- Posts

- La Garde Ecossaise Historical Fiction and Early Modern Studies Newsletter

La Garde Ecossaise Historical Fiction and Early Modern Studies Newsletter

No. 16 Intelligence in contemporary sources: four key examples.

Welcome

A warm welcome to the La Garde Ecossaise Historical Fiction newsletter – this is your fortnightly update on the novel series and early modern studies.

Latest Releases from La Garde Ecossaise

Podcast, Season 2 Ep 3 The World of the Early Modern Marksman.

Podcast Season 2 Ep 4 The World of Spies and Intelligence.

Podcasts available on Spotify, Apple Podcasts and YouTube.

Quote

‘One of the key signs that I was becoming a trusted member of the group was my introduction to their highly secretive codes of intelligence. I can only provide limited details here, but I will tell the reader enough to enable them to understand our stories’.

La Garde Ecossaise p.101.

Cypher Letter (Gencraft AI).

Early Modern Digest

Project to rebuild lost renaissance garden https://www.finestresullarte.info/en/news/massa-reborn-the-ducal-pomerio-the-project-to-rebuild-the-lost-renaissance-garden

Wittenberg, the birthplace of the Protestant reformation https://www.dw.com/en/wittenberg-germany-birthplace-of-the-protestant-reformation/video-73417563

A story of passion and power George Villers and James I https://www.rmg.co.uk/stories/royal-history/power-passion-george-villiers-james-i

Searching for Louis XIVs lost treasure https://www.superyachttimes.com/yacht-news/treasure-hunt-panama

Detox treatment 17th century style https://aeon.co/videos/drinking-wine-from-toxic-cups-was-the-17th-centurys-own-dubious-detox-treatment

Did you know?

Wooden wagonways used to move coal from the mines in Newcastle in the 17th century laid the foundations for the development of rails for steam trains in the nineteenth century. Read more about it here https://www.northeastmuseums.org.uk/stephensonsteamrailway/the-dawn-of-the-railways

Monument to the Wooden Waggonways in Sunderland, England. Wooden waggonways monument by Oliver Dixon, CC BY-SA 2.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Feature Article Intelligence in Contemporary Sources: Four Key Examples.

Throughout early modern Europe there were complex and hidden networks of spies and exchanges of intelligence on a wide variety of matters. In the podcast I introduce you to four main kinds of intelligence: domestic, military, diplomatic and foreign intelligence. I also briefly introduce you to the main methods of communication between spies; the use of lemon juice and cyphers in letters of intelligence.[1] If you have missed the podcast you can catch up here.

But how do historians spot secret intelligence in contemporary sources? What does it look like?

We must also consider some key questions when finding and consulting such material:

· Who is the letter sent to? (e.g. Spymaster, contact in the network, unwitting recipient – intercepted correspondence).

· Who is the letter sent by? (e.g. Contact in the network, double agent, unwitting sender – intercepted correspondence, diplomat).

· Is it a direct message or intercepted correspondence?

· What methods do they use to communicate the message? (cypher, lemon juice, oral or written).

· Is it a copy of a letter of intelligence or an original letter? (In some source collections you may be fortunate to find both).

· What is the context of the intelligence? What are the events going on at the time when the intelligence is being compiled, written and/or sent?

· Is the intelligence in a language other than the native language of the network? (especially when examining diplomatic and foreign correspondence).

· Can we verify or corroborate the information contained in the letter?

· Did the letter reach its desired recipient?

· What impact, if any, did the intelligence have on events at the time?

· Was the intelligence ever made public, either by mistake or design?

· How did these letters of intelligence survive? Why can we read them today?

This feature article will show how these questions work in practice as we examine four pieces of intelligence in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries:

Domestic Intelligence: A letter from ___to Mr. John Fleming June 1638 from the Calendar of State Papers Domestic 1637-8.

Military Intelligence: Dudley Bradstreet’s intelligence about Hanoverian troop movements at the Jacobite military council during the 1745 Jacobite rebellion.

Foreign Intelligence: A letter from Colonel John Bampfield double-agent for John Thurloe.

Diplomatic Intelligence: A letter from the Venetian ambassador about events in England from the Calendar of Venetian State Papers.

Please click on the linked text to get direct access to the sources under discussion.

Domestic Intelligence: A letter from ___to Mr. John Fleming June 1638 from the Calendar of State Papers Domestic 1637-8. pp. 524-525.

There are two copies the original letter of intelligence in the British State Papers. These are copies of letters of intelligence from an unnamed correspondent to Mr. John Fleming in Edinburgh. The original letter pinpoints the exact house that Mr. Fleming lives in to ensure that the letter is delivered to the right place. This excerpt is from the Calendar of State Papers which gives summaries and brief quotations from the British state papers held in The National Archives at Kew. Therefore, although this letter was intended for Mr. John Fleming based in Scotland copies of the letter can be found in Kew. If you have institutional access, you may be able to view the copied letters here. It is unclear whether Mr. Fleming is part of a spy network or whether this is intercepted correspondence. The excerpt from the Calendar of State Papers and offers some very interesting details about how the letter was written ‘partly of cyphers, expressed in numbers, and partly of written words, the greater number of which last are nullities’.[2] Furthermore the editors of the Calendar of State Papers give some interesting details about how the letter was laid out, written on one page, ‘At its four corners there are, 1st a perpendicular line; 2nd a horizontal line; 3rd a horizontal line; and 4th a perpendicular line, which last occurs at the corner where the signature ordinarily stands’.[3] Clearly the author of the original letter did not wish to be identified.

The following letter, which is a copy of the preceding letter, is a working copy likely to have been written by a spy working for the government who was tasked with decoding the letter. As it is described ‘disposed in numbered lines, and with the nullities underscored’.[4]

The final copy of the letter is a rough decoding of its contents with some of the numbers undeciphered. Clearly not all the numbers could be decoded. Yet its contents are now revealed, and it is a letter which discusses the Scottish Privy Council and its struggles to deal with a rebellion over the Scottish Prayer Book and the gathering support for the Charles Is opponents known as the Covenanters. It highlights that it was known within Scottish society that the King and the Scottish Privy Council were struggling to contain and quell the rebellion and that the Scottish Privy Council were making plans for military assistance from Ireland.[5]

Military Intelligence: Dudley Bradstreet’s intelligence about Hanoverian troop movements at the Jacobite military council during the 1745-1746 Jacobite rebellion.

The pivotal role that deliberately false military intelligence had on the outcome of the 1745-1746 Jacobite rebellion will be very familiar to those who know the key events of the ‘45. Yet, it is one of the few examples where we can see how military intelligence had an enormous impact on the outcome of a conflict. It is also a rare example, where we know that oral, rather than written intelligence, played a key role in events.

As Christopher Duffy states in his excellent account of the 1745 Jacobite Rebellion, Dudley Bradstreet (aka Oliver Williams) was ‘a spy and confidence trickster’ who had been given papers and a new identity by the Hanoverian state. He met with the Duke of Cumberland on the 2nd of December and rode into Derby on the 5th of December 1745 stating that he wished to join the Jacobite cause. His arrival was rather opportune as the Jacobite military command which included Prince Charles Edward Stuart were arguing whether to push onto London and claim the British throne from the Hanoverian dynasty or to retreat back to Scotland. There was a lack of visible support for the Jacobite cause from the English populace or outside assistance from the French. Lord George Murray, the Prince’s principal commander advised caution about marching on to London but the Prince was determined to push on. One of the key elements of doubt and debate within the Jacobite Council at Derby was the exact location of the Duke of Cumberland’s forces. Enter Dudley Bradstreet.

‘[Bradstreet] declared that the Duke of Cumberland was about to cut across their path of retreat from Lichfield with 8-9000 men, while the Duke of Richmond harried their right flank with his cavalry, and – a total fiction - that Ligonier or Hawley would oppose them frontly with a third force from Northampton’.[6]

Believing that they would be encircled and blocked from getting to London, Jacobite forces retreated. Thus, potentially altering the whole course of British history. To this day, the events of the Jacobite Council at Derby is one of the great ‘What if?’ moments of British history and even alternative histories have been written suggesting what might have happened had Charles Edward Stuart and his army continued onwards to London.[7]

Prince Charles Edward Stuart. William Mosman, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

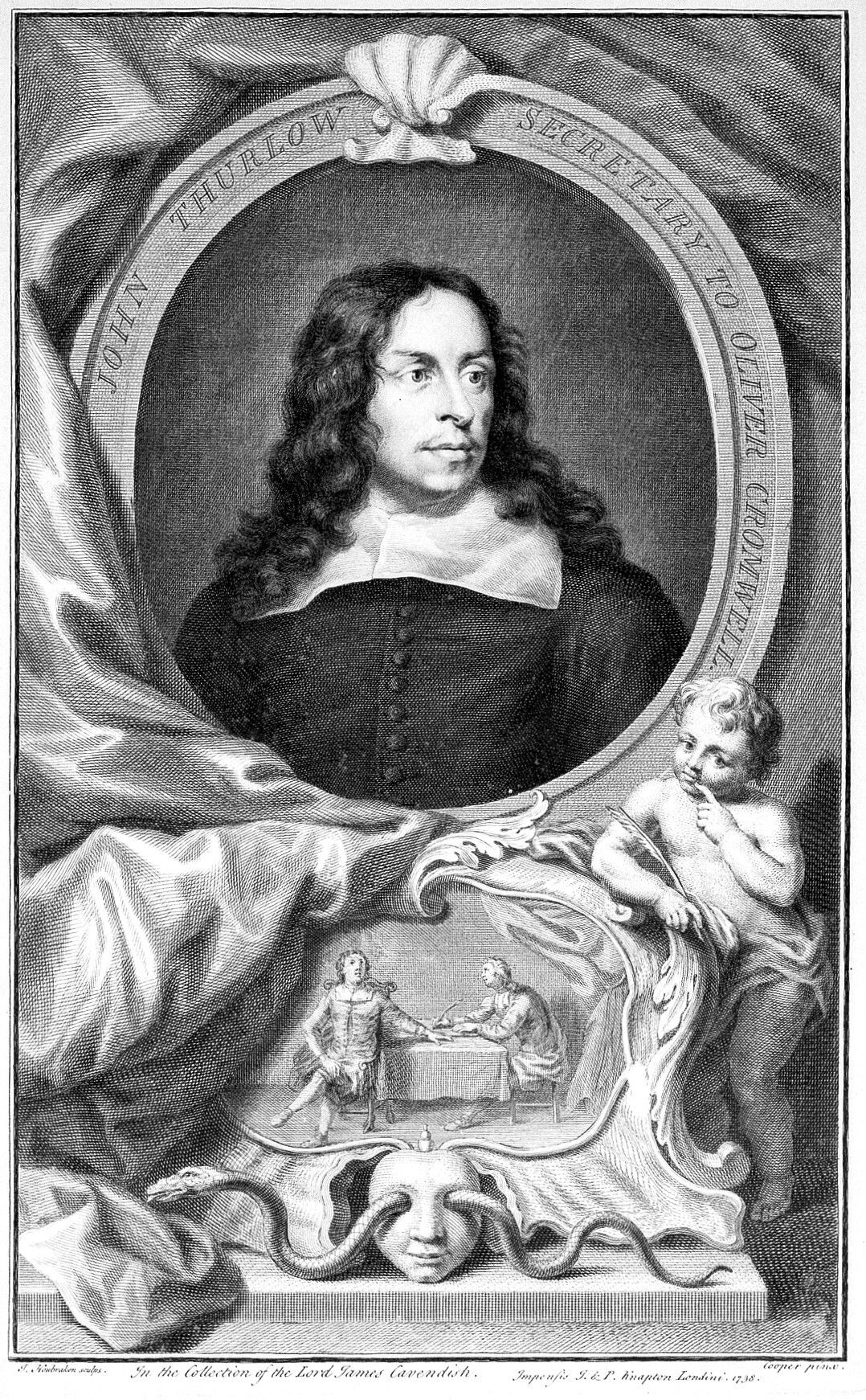

Foreign Intelligence: A letter from Colonel John Bampfeild double-agent for John Thurloe, spymaster of the Protectorate living amongst exiled Royalists in Europe.

The Thurloe State Papers were published in the eighteenth century and are one of the most important sources of the English Republic. As discussed in the podcast, the English Republic which governed Britain and Ireland between 1649 and 1660 was under constant threat by many enemies, both at home and abroad, who never accepted a regime which governed the country without a monarch. Royalists living at the exiled King’s court in Europe were a threat to the English Republic’s existence through their funding of secret Royalist groups such as The Sealed Knot and the Action Party which planned uprisings and assassinations against the English Republic. John Thurloe was not only the Secretary of State under Oliver Cromwell, but he was also the regime’s spymaster. Thurloe’s state papers contain large amounts of secret intelligence covering a wide variety of subjects from both home and abroad, interviews with suspects, reports on planned and active risings and intelligence obtained via diplomatic correspondence and from agents working for the English Republic about Royalist activities in Europe.[8]

John Thurloe. The Wellcome Collection. See page for author, CC BY 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

It is likely that Thurloe handled several double agents for the English Republic and one of the most notorious was Colonel Joseph Bampfield, which as stated in the podcast is one of the key inspirations behind our very own spymaster in the La Garde Ecossaise novels, Timothy Gray. Colonel Joseph Bampfield, a former Royalist officer living in exile with the Royalist court in France, became a double-agent working for Thurloe passing on intelligence about Royalist activities in Europe and Royalist plots within Britain itself.[9]

We have a few letters from Colonel Joseph Bampfield in the Thurloe State Papers including this one from January 1655 in which he is informing Thurloe of a notable movement in arms and ammunition as well as the exiled Royalist court’s reaction to failed plots. Notice that he informs Thurloe that some letters have miscarried, such was the precarious nature of postal networks and letter carrying in Britain and Europe at the time, especially in relation to espionage.[10]

Diplomatic Intelligence: A letter from the Venetian ambassador about events in England from the Calendar of State Papers and Manuscripts relating to English affairs existing in the Archives and Collections of Venice and Northern Italy.

Diplomatic intelligence was immensely important throughout early modern Europe as it informed states about events in countries where their ambassador was resident as well as informing their monarchs and rulers about the progress of treaties between countries. Diplomats also had their own internal networks where ambassadors from the same country would contact each other for mutual support and information.[11]

The Calendar of State Papers Venetian as it is commonly known amongst historians, are calendars of the reports sent by the various ambassadors of the Republic of Venice to their superiors during the early modern period. Not only do they detail the experience of being an ambassador and the various treaties and agreements, but they are also a treasure trove of fascinating information about domestic and foreign affairs relating Britain at this time.

The Venetian ambassador reports his meeting with King James I before his coronation in England in 1603:

‘On Saturday last I had an audience of the King, and in order to approach the subject of my precedence cautiously I said that I had long desired to find myself in his presence to offer my congratulations on his sound health, in spite of the false rumours that were spread about him. I had hoped to perform that duty when his Majesty had honoured me with an invitation to attend the ceremony of Coronation-Day, and I, therefore, felt the more deeply the vain pretensions of the Archduke’s Ambaseador, as they had deprived me of that privilege, and also of the opportunity to testify’.[12]

This passage is illuminating for two reasons; we find out that in England, prior to James Is coronation there were false rumours of King James Is ill-health. We also discover that the ambassadors are jockeying for position at the King’s coronation as a matter of diplomatic favour and standing.

King James I. The Royal Collection. Paul van Somer I, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

I hope you have enjoyed the latest edition of the newsletter. If you are reading this newsletter on the web and have any questions please leave a comment below or you can email me at [email protected]

A Journey through Early Modern History. The La Garde Ecossaise Historical Fiction Novels. An introduction to early modern history as told through the power of historical fiction.

BUY from Amazon, Barnes and Noble and other retailers. Visit the official website for further details.

SUBSCRIBE to the official newsletter here to receive free short original articles and news on early modern history.

[1] La Garde Ecossaise Historical Fiction Podcast https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rrX3liFQqms; Nadine Akkerman and Pete Langman, Spycraft : Tricks and Tools of the Dangerous Trade from Elizabeth I to the Restoration (New Haven, 2024). The best introduction to the skills of spycraft in early modern Britain.

[2] John Bruce and William Douglas Hamilton eds., Calendar of State Papers Domestic Charles I 1637-8 (London, 1871) 524-525. [Hereafter CSPD 1637-8].

[3] CSPD 1637-8 524.

[4] CSPD 1637-8 524.

[5] CSPD 1637-8 524-525. For an introduction to the context of this letter see David Stevenson, The Scottish Revolution 1637-1644 (Edinburgh, 2003) 88-102; Peter Donald, An Uncounselled King: Charles I and the Scottish Troubles 1637-1641 (Cambridge, 1990) 78-93.

[6] Christopher Duffy, The ’45 (London, 2003) 300-301; A.J. Youngson, The Prince and the Pretender: Two Views of the ’45 (Edinburgh, 1996) 112-116, for a fuller consideration of the military context surrounding the council at Derby.

[7] Duffy The ’45 301; Charles Petrie, ‘If: A Jacobite Fantasy’ http://www.jacobite.ca/essays/if.htm accessed 04/09/2025.

[8] Thomas Birch ed., A Collection of the State Papers of John Thurloe (London, 1742); See Alan Marshall, Intelligence and espionage in the English Republic 1600-60 (Manchester, 2023); D.L. Hobman, Cromwell’s Master Spy: A Study of John Thurloe (London, 1961) for an insight into Thurloe’s enormous workload. For the exiled Royalists and their involvement in conspiracy against the English Republic see, Geoffrey Smith, Royalist Agents, Conspirators and Spies: Their Role in the British Civil Wars, 1640-1660 (Farnham, 2011); David Underdown, Royalist Conspiracy in England 1649-1660 (New Haven, 1960); Geoffrey Smith, The Cavaliers in Exile 1640-1660 (London, 2003).

[9] Underdown, Royalist Conspiracy in England 62-63; Smith, Royalist Agents, Conspirators and Spies 176-178; Smith, Cavaliers in Exile 146-147.

[10] Birch, Thurloe State Papers Volume IV [From Col Bampfield] 87-88. https://archive.org/details/collectionofstat03thur/page/86/mode/2up?q=bampfield accessed 04/09/2025.

[11] For an introduction to all these aspects within the context of 1650s Britain see Kirsteen M. MacKenzie, ‘The Waiting Game: Cromwellian Diplomacy, the Foreign Experience’ Cromwelliana Series 2 16 (2009) 95-110.

[12] Horatio Brown ed., Calendar of State Papers and Manuscripts relating to English affairs existing in the Archives and Collections of Venice and Northern Italy 1603-1607 (London, 1900) 341-342. https://archive.org/details/dli.ministry.01116/page/341/mode/2up?q=Coronation accessed 04/09/2025.

Reply